Boat Propeller Selection & Education

To start off this journey, we’ll revisit the basics and then dive deeper on propeller form, fit and function.

Back in the 1980s, Quicksilver Accessories published a book entitled, Everything You Need to Know About Propellers. It was a bible for folks like us who were learning about a very complicated and critical component that is used in diverse applications and environments. Much of the information we will cover is from the fifth edition of this knowledge guide.

The guide includes some interesting history on the development of propellers.

Prop Terminology.

Anyone who has shopped for a propeller has been exposed to terms describing the various design functions. I remember when props evolved from two to three blade designs. And when replacing the prop on the family runabout, all you needed to know was the diameter and pitch.

In the go-fast world of performance boating, diameter and pitch are important, but many other factors come into consideration as well. Its all about efficiency. Diameter, pitch, rake, cup, rotation, number of blades, blade thickness, blade contour, skew, ventilation, cavitation, elevation, and angle of attack all come into play when propping a boat for maximum performance and efficiency.

We'll get deeper into these facets of propeller design that affect boat performance in this next section

– Part 1: Terminology.

Propellers are available in both right-hand and left-hand rotation. Most single engine outboard and sterndrive powered boats use right-hand rotation propellers. A right-hand rotation propeller will spin clockwise when pushing the boat forward, while a left-hand propeller will spin counter-clockwise.

Number of Blades

The most popular propellers used for recreational boating have three or four blades. Three-blade props are efficient and do a good job of minimizing vibration. Four blade props are popular for suppressing vibrations even further while improving acceleration by putting more blades in the water.

Diameter

In “prop speak,” diameter is the distance across a circle made by the blade tips as a propeller rotates. The proper diameter is determined by the power that is delivered to it and the resulting propeller rpm.

Type of application is also a factor. The amount of propeller in the water (partially surfaced vs fully submerged) plays a role in determining diameter. The more a propeller is surfacing above the water, the larger the diameter needs to be (so what’s left under water can still push). On rare occasions, diameter may be physically limited by drive type or in close, staggered engine installations where tips can touch.

Within a specific propeller style, diameter is usually larger on slower boats and smaller on faster boats. Similarly, for engines with a lower maximum engine speed (or with more gear reduction), diameter will tend to be larger. Also, diameter typically decreases as propeller blade surface areas increase (for the same engine power and rpm). A four bladed prop replacing a three blade of the same pitch will typically be smaller in diameter.

Physical limits

Mercury Racing engines fitted with the Bravo One XR or Bravo Three XR drives are designed for props up to 16-inches in diameter. Bravo One XR drives fitted with the short Sport Master gearcase accepts props up to 15-1/4 inch in diameter. Sterndrive engines with surface piercing M6 or M8 sterndrives run cleaver props up to 18-inches in diameter. Our 4.6L V-8 250R and 300R FourStroke outboards as well as the 400R Verado accept props up to 16-inches in diameter.

Pitch is the distance a propeller would move in one revolution if it were moving through a soft solid, like a screw in wood. When we list an outboard four-blade Pro Max prop as a 14-1/2 X 32, we are saying it is 14-1/2 inches in diameter with 32-inches of pitch.

Pitch is measured across the face of a propeller blade. Actual pitch can vary from the pitch number stamped on the prop. Modifications made by propeller shops may alter the pitch. Undetected damage from a submerged object may result with a bent blade, altering the pitch as well.

There are two common types of pitch; constant and progressive. Constant pitch means the blade pitch is the same – from the leading edge to trailing edge. Progressive pitch, referred to as blade camber, starts low at the leading edge and progressively increases toward the trailing edge. The pitch number, “32” in the Pro Max example, is the average pitch over the entire blade.

Pitch is like another set of gears. Since an engine needs to run within its recommended maximum rpm range, proper pitch selection achieves that rpm. The lower the pitch, the higher the engine rpm. Mercury Racing propellers are designed so that a one-inch change in pitch results in a 150 rpm change in engine speed.

A lower pitch propeller may provide greater acceleration for water sports activities, but your top speed and fuel efficiency may suffer. If you run at full throttle with a prop selected for acceleration and not top-end speed, your engine rpm may be too high, placing an undesirable stress on the engine. If you select too high of a pitch, your engine may lug at a lower rpm – which can also cause damage. Acceleration will be slower as well. It will be reduced further with a full load of fuel and maximum capacity of people on board.

Proper pitch selection allows the engine to operate near the top of its recommended rpm range at light load (1/2 fuel tank and two people). Using this pitch selection method, the engine usually operates near the low end of the recommended engine operating range when the boat is fully loaded (full fuel tank, boating gear, full live wells, and maximum capacity). Full load engine speed is usually reduced 200 to 300 rpm. The power output of naturally aspirated engines can be affected by high heat and humidity which is another factor that can reduce engine speed by 200 to 300 rpm.

The Mercury Racing Prop Slip Calculator App is very helpful in determining the proper pitch for your application.

Smart, pressure charged engines like the supercharged 400R outboard and our turbocharged QC4 sterndrives will auto-regulate power output for heat and humidity. Adaptive Speed Control, a standard feature on our 250R and 300R outboards, is another factor to consider when dialing in your boat for maximum power and top-end speed.

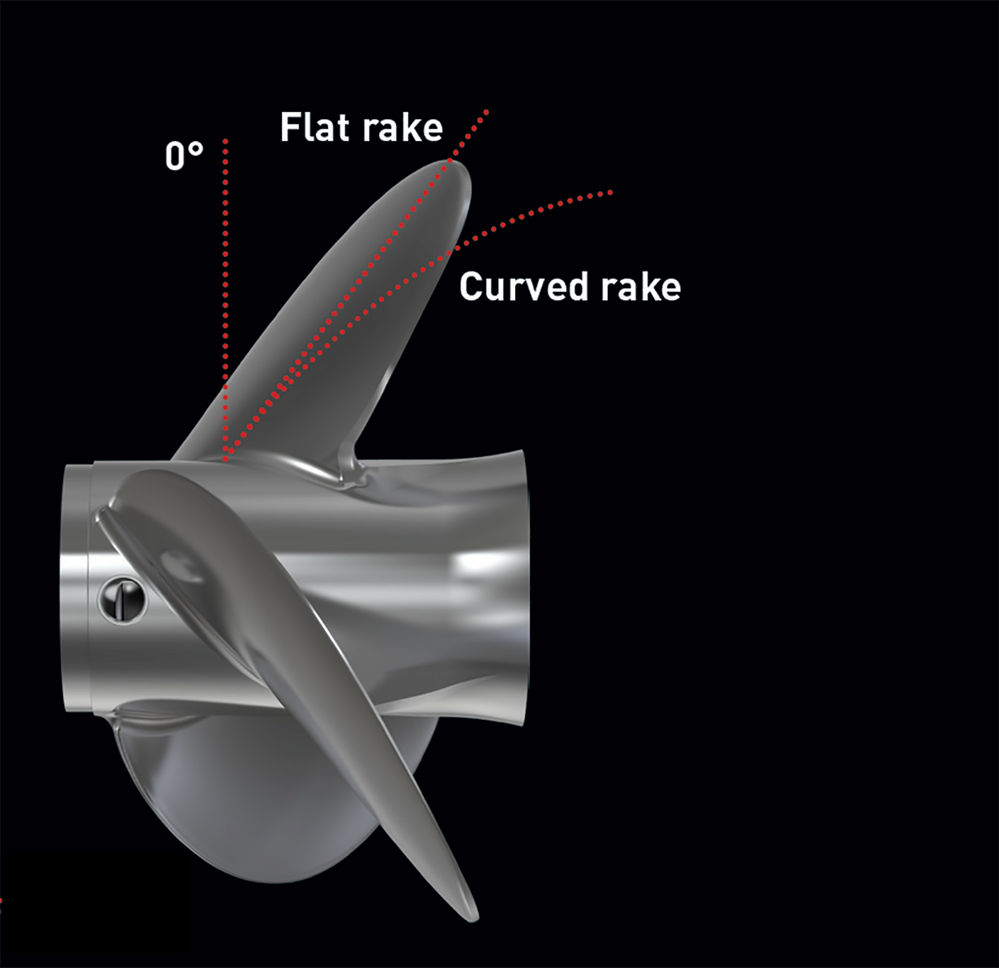

In this next section, we will discuss blade rake.

-Part 2: Blade Rake

On lighter, faster boats with a high prop shaft, increased rake often will improve performance by holding the bow higher. This results in higher speeds due to less hydrodynamic hull drag. However, on some very light boats, more rake can cause too much bow lift. That will often make a boat less stable. Then, a lower rake propeller (or a cleaver style for outboard) is a better choice.

Looking at examples:

A runabout with Alpha sterndrive usually performs best with a lower rake Black Max or Vengeance pushing the boat. The aim is broad capability and utility for many recreational activities.

A lighter weight runabout with Alpha drive may increase performance with higher rake Enertia propellers lifting the bow offering less wet running surface (lower drag).

Bass boats can vary widely because of the design differences among hulls in the market. Mercury offers high rake propellers such as the Tempest Plus and Fury for these applications. Mercury Racing specialty props for the bass market include the Lightning E.T., Bravo I FS, Bravo I XS and Pro Max.

The Bravo XR drive, used with higher horsepower multi-length and weight applications, typically use props with high rake and large blade area — such as the Bravo I and Maximus.

Our Pro Finish 5-blade CNC Cleaver prop is available with 15, 18, or 21-degree rake.

Performance applications using Mercury Racing’s CNC Pro Finished Cleavers with M6 or M8 drives have three rake choices: 15, 18 or 21 degree. Most “V” and step “V” bottom boats utilize a 15 degree rake — unless the center of gravity is forward of the helm; then, 18 degree rake works best. The higher rake helps lift the bow — positioning the boat to ride appropriately on the steps. Air entrapment hulls (catamarans and tunnel hulls) pack air and lift during forward motion; they typically use props with 15 to 18 degree rake — since air pressure does most of the lifting.

The 15-degree and 18-degree rake Pro Finish CNC Outboard Cleaver is being used in a variety of applications including bass boats, performance center consoles and catamarans.

Your head probably hurts by now, so we'll discuss blade cup in Part 3.

-Part 3: Blade Cup

Originally, cupping was done to gain similar benefits as you get from progressive pitch or higher blade rake. In fact, cupping reduces full-throttle engine speed 150-300 RPM below the same pitch prop with no cup. The location of cup on the blade determines the affect it has on performance. When the cupped area intersects pitch lines, pitch increases. Cupping in this area will reduce engine RPM. Cupping can also prevent prop cavitation or blow out. Blade rake can be increased when the cup intersects the rake lines. Slip is a measurement of propeller efficiency as it turns through the water, the normal range is 10-15%. Most racing and performance boats slip can be as low as 5-7% where as performance vee and step vee bottom boats with high X dimension (outboard engines or sterndrives mounted high) can see slip as high as 20-22% at WOT

Cleaver Cup.

Adjusting cup on cleaver-style propellers is more difficult. The trailing edge is very thick and runs straight out on the rake line. Pitch can be altered some by grinding away some of the cup. Rake may also be altered slightly. The rake can be reduced by decreasing the cup near the tip of the blade. Rake can be increased by reducing the cup near the prop hub. Remember that any change in cup affects engine RPM. The Bravo I propeller family is a good example of how cup changes RPM and the attitude of the boat we'll discuss blade configurations and factors that effect propeller efficiency in Part 4.

-Part 4: Blade Efficiency

Rotation.

Propellers come in both right and left-hand rotation. Standard rotation for both outboards and sterndrives is right-hand: the prop spins clockwise when in forward gear. Left-hand props spin counter clockwise. Left-hand props are typically used with multi-engine applications. The counter-rotation prop works to balance (or reduce) the torque effects from the right-hand prop. Most twin engine applications are setup with the props “turning in”; the port engine spinning right-hand and the starboard engine spinning counter clockwise.

Hull types and designs respond differently to prop rotations. Some need additional stern lift to reach maximum efficiency and performance. To obtain this, the rotation of both propellers is set up, so they rotate away from each other. We call this turning the props out. The left-hand rotation prop is on the port side and the right-hand rotation is on the starboard side.

For example, a high-speed catamaran loaded with gear and passengers often runs best with 5-blade cleaver props with 15-degree rake. Turning the props in pulls the stern down, enabling the boat to float over chop. With lighter loads and ideal conditions, the same cat can gain 6 to 8 mph when using 18-degree rake, 5 blade cleavers “turned-out.”

Number of Blades

In theory, two blade props are most efficient since they have the least amount of surface dragging through the water. Two blade props are commonly used on lower horsepower outboards and trolling motors. Three -blade and four-blade props are the most common designs used today. The added blades reduce vibration while maintaining most of the efficiency of a two-blade design at a convenient size and reasonable cost.

Racers and performance boaters raise sterndrive mounting heights (x-dimensions) on ventilated, stepped hulls. The steps create air bubbles, raising the hull off the water on a drag-reducing cushion. This, combined with reduced drag from the higher drive heights, improves hull efficiency. This trend has spawned an evolution of prop designs featuring four, five and even six blades. The additional blade surface helps offset slip induced by air bubbles flowing from the ventilation steps toward the props.

Blade Thickness

For efficiency, blades should be as thin as possible to reliably handle a particular power range. A cross section of a typical constant pitch prop blade reveals a flat section on the positive (pressure) side and an arc surface on the negative (suction side) of the blade. Edges are usually 0.06″ to 0.08″ (1.5 mm to 2.0 mm) thick for aluminum props, thinner for stainless steel.

The blade cross section on surfacing props such as our T.E. Cleaver and Pro Finish CNC Cleavers is wedge shaped. The thick trailing edge adds strength. Surface air ventilates a low-pressure cavitation pockets behind the trailing edge, enhancing efficiency. The contour or shape of most propeller blade tips (other than cleaver) are round.

Next we'll discuss propeller slip more thoroughly in – Part 5.

-Part 5: Slip

Propeller blades work like wings on an airplane. Wings carry the weight of the plane by providing lift; marine propeller blades provide thrust as they rotate through water. If an airplane wing were symmetrical (air moves across the top and bottom of the wing equally), the pressure from above and below the wing would be equal, resulting in zero lift. The curvature of a wing reduces static pressure above the wing — the Bernoulli effect — so that the pressure below the wing is greater. The net of these two forces pushes the wing upward. With a positive angle of attack, even higher pressure below the wing creates still more lift.

Similarly, marine propeller blades operating at a zero angle of attack produce nearly equal positive and negative pressures, resulting in zero thrust. Blades operating with an angle of attack create a negative (lower or pulling) pressure on one side and a positive (higher or pushing) pressure on the opposite side. The pressure difference, like the airplane wing, causes lift at right angles to the blade surface. Lift can be divided into a thrust component in the direction of travel and a torque component in the opposite direction of prop rotation.

Prop Slip

Slip is the difference between actual and theoretical travel through the water. For example, if a 10-inch pitch prop actually advances 8-1/2 inches per revolution through water, it is said to have 15-percent slip (8-1/2 inches is 85% of 10-inches). Similar to the airplane wing, some angle of attack is needed for a propeller blade to create thrust. Our objective to achieve the most efficient angle of attack. We do this by matching the propeller diameter and blade area to the engine horsepower and propeller shaft RPM. Too much diameter and or blade area will reduce slip, but at a consequence of lower overall efficiency and performance.

Calculating Rotational Speed, Blade Tip Speed and Slip

Our propeller engineers study props at the 7/10 radius (70% of the distance from the center of the prop hub to the blade tip). The 7/10 radius rotational speed in MPH can be calculated as follows:

Forward speed is shown by an arrow in the direction of travel. The length of the arrows reflect speed in MPH for both the measured speed and the theoretical (no slip) forward speed.

Prop Slip Calculator

Today, you can get all of your prop information with Mercury Racings Prop Slip Calculator App. Download it for free from Google Play Store or Apple iTunes.

-Part 6: Barrel Length

The different barrel length options for the Lab Finished Maximus LT and ST propellers have been a used for years to fine tune stern lift on boats powered by twin sterndrive engine.

A long propeller barrel can negatively impact top-speed performance in many fast boat applications when stern lift created by the barrel causes the boat to run too flat. The Mercury Racing Bravo I FS, Bravo I XS, Bravo I OC, MAX5, MAX5 ST, and Maximus ST all feature shortened and tuned barrels to dial back stern lift. The Bravo I OC and MAX5 ST represent the most extreme versions of this treatment, featuring very short barrels that perform especially well when an ultra-lightweight boat is paired with high-horsepower outboard power.

If you are up to speed on our previous Prop School Sections, you will know that the barrel is not the only part of the propeller that provides lift. But if a propeller is generating too much lift due to diameter or blade count, the barrel is often the first part of the propeller to “hit the chopping block.”

The MAX5 ST is suitable for lightweight bass boats and catamarans featuring the 250R, 300R, and 450R outboards.

The Bravo I OC is specifically designed for twin engine two stroke powered catamarans.

-Part 7: Propeller Finishes

Mercury Marine produces a broad selection of Standard Finish propellers that deliver outstanding performance for recreational boating. To serve high-performance and racing customers, Mercury Racing offers its 20 propeller lines in two finish levels: Pro Finish and Lab Finish. The most popular Mercury Racing propeller models, the Bravo I and Revolution 4, are offered in both Pro and Lab Finishes. The Bravo I FS, LT, XS, XC, and Revolution 4 XP are all Pro Finish propellers.

In most applications switching from a Standard to Pro Finish propeller will permit stepping up one inch of pitch due to the ability of the Pro Finish to generate higher RPM. The opportunity to run a propeller with more pitch can produce a 2- to 5-mph increase in top end-speed – simply from bolting on the propeller.

Mercury Racing Lab Finish propellers follow a similar journey but are taken to the next level with additional blade thinning, which creates a sharper wedge that cuts through the water with less power-robbing drag and, once again, an increase in top-end RPM and a step up in pitch by about one inch with a corresponding gain in top speed, compared to a Pro Finish model. Mercury Racing Lab Finish props are especially effective on lighter-weight high-performance boats capable of running above 80 mph. Lab Finish props are durable but the ultra-crisp blade edges must be maintained to retain peak performance.

Mercury Racing offers a diverse line of propellers that are continually tested and improved in the most demanding environments. Mercury Racing backs its props with a one-year factory warranty, which also covers any and all damage done to the engine upon propeller failure.

The Bravo I FS has taken the bass, walleye, and multi species market by storm, in part because of the top end speed gains from its Pro Finish.

The only propeller not built exclusively by hand is the CNC Cleaver, which features our Lab Finish specifications for maximum top end speed.

-Part 8: How to Reach Your Performance Goals

Propeller selection can be a mind-boggling exercise. Start the process by following these basic tips.

The ever-changing variety of hull designs, engine configurations, and general boat capabilities place new demands on propeller performance. Today with Mercury Marine and Mercury Racing offering over forty combined stainless steel propeller lines the options facing a propeller customer can be overwhelming. Consider these three key points to best select the propeller that will help you meet your performance goals:

1. Have a measurable performance goal, or rank the performance attributes that are most important for your specific boating needs. Top-end speed, hole shot, mid-range fuel economy, rough-water handing, certain lifting characteristics, and low-speed maneuverability are the most common performance criteria any boat owner could consider a priority. Dialing in boat performance can be tricky because everyone uses their boat differently. A water sports enthusiast, a competitive angler, and an offshore racer each have a very different perspective on ideal performance, and at the micro level are differences in how a walleye boat and a bass boat perform, or a high-performance catamaran versus a vee hull. In any situation running the ideal propeller, or the wrong propeller, can have a significant impact on performance and how much you enjoy the boat.

2. Selecting an ideal propeller usually involves some testing and trial and error, but before that can happen you need to establish some very basic baseline data. Make sure your tachometer and speedometer are functioning properly and accurately. From there, a simple first exercise would be to run the boat at wide open under normal operating conditions and load. Record engine RPM and top speed. If RPM is below the recommended operating range or hitting the rev limiter, you can adjust pitch to improve performance. Measuring RPM and boat speed at your normal cruising speed is also important, and an instance where the Mercury Racing Prop Slip Calculator can be used to see how well the propeller is hooking up.

3. Familiarize yourself with the current propeller on the boat. Make note of the blade count, length of the barrel and whether or not the barrel is flared, the size of the blades, etc. Are the blades dull and worn or do they look brand new? Reference our 8-part Propeller School blog series to learn how the different parameters of your propeller are affecting performance.

Once you have a clear performance goal, baseline data, and a very basic understanding of what type of propeller you currently have and how it is affecting performance, you can narrow down the various options available to help you reach your specific performance goals. For expert advice or any questions regarding performance propellers Contact us Today!

-The End

We want to give special thanks to everyone at Mercury Racing for making this Prop School and providing all this info.

Credits:

Propeller Selection & Education

Choosing the correct propeller is one of the most important factors in overall boat performance. The right prop affects acceleration, top speed, fuel efficiency, engine load, and long-term reliability.

This page is designed to help boat owners understand how propeller selection works and why proper sizing and setup matter for real-world use.

Why Propeller Selection Matters

A propeller that is improperly sized or matched can lead to:

• Reduced performance and handling

• Increased fuel consumption

• Excessive engine wear

• Poor acceleration or top-end speed

• Difficulty reaching recommended operating ranges

Proper propeller selection ensures the engine operates within manufacturer specifications while delivering balanced performance for how the boat is actually used.

Key Factors That Affect Propeller Choice

Propeller selection is not one-size-fits-all. Several factors influence the correct setup, including:

• Boat type and hull design

• Engine horsepower and torque characteristics

• Gear ratio

• Typical load and passenger weight

• Intended use such as cruising, fishing, towing, or performance

• Desired balance between speed, efficiency, and handling

Understanding these variables helps narrow down the best propeller options.

Pitch, Diameter, and Blade Design

Small changes in pitch or diameter can significantly impact performance. Blade count and design also play a role in grip, lift, and smoothness.

Education around these elements helps owners understand why adjustments are sometimes recommended during service or performance evaluations.

Professional Evaluation Makes the Difference

While general guidance is helpful, proper propeller selection is best confirmed through hands-on evaluation. Performance testing, engine data, and real operating conditions often reveal adjustments that aren’t obvious on paper.

Gregor’s Marine assists boat owners with propeller evaluation, recommendations, and setup based on practical experience and manufacturer guidelines.

Supporting Long-Term Performance

The goal of proper propeller selection is not just speed. It’s protecting the engine, improving drivability, and ensuring consistent performance across different conditions.

Educated propeller choices reduce stress on propulsion systems and help owners get the most out of their boats over time.